An example of our method deployed on a Clearpath Jackal ground robot (left) exploring a suburban environment to find a visual target (inset). (Right) Egocentric observations of the robot.

An example of our method deployed on a Clearpath Jackal ground robot (left) exploring a suburban environment to find a visual target (inset). (Right) Egocentric observations of the robot.

Imagine you’re in an unfamiliar neighborhood with no house numbers and I give you a photo that I took a few days ago of my house, which is not too far away. If you tried to find my house, you might follow the streets and go around the block looking for it. You might take a few wrong turns at first, but eventually you would locate my house. In the process, you would end up with a mental map of my neighborhood. The next time you’re visiting, you will likely be able to navigate to my house right away, without taking any wrong turns.

Such exploration and navigation behavior is easy for humans. What would it take for a robotic learning algorithm to enable this kind of intuitive navigation capability? To build a robot capable of exploring and navigating like this, we need to learn from diverse prior datasets in the real world. While it’s possible to collect a large amount of data from demonstrations, or even with randomized exploration, learning meaningful exploration and navigation behavior from this data can be challenging – the robot needs to generalize to unseen neighborhoods, recognize visual and dynamical similarities across scenes, and learn a representation of visual observations that is robust to distractors like weather conditions and obstacles. Since such factors can be hard to model and transfer from simulated environments, we tackle these problems by teaching the robot to explore using only real-world data.

Formally, we studied the problem of goal-directed exploration for visual navigation in novel environments. A robot is tasked with navigating to a goal location ![]() , specified by an image

, specified by an image ![]() taken at

taken at ![]() . Our method uses an offline dataset of trajectories, over 40 hours of interactions in the real-world, to learn navigational affordances and builds a compressed representation of perceptual inputs. We deploy our method on a mobile robotic system in industrial and recreational outdoor areas around the city of Berkeley. RECON can discover a new goal in a previously unexplored environment in under 10 minutes, and in the process build a “mental map” of that environment that allows it to then reach goals again in just 20 seconds. Additionally, we make this real-world offline dataset publicly available for use in future research.

. Our method uses an offline dataset of trajectories, over 40 hours of interactions in the real-world, to learn navigational affordances and builds a compressed representation of perceptual inputs. We deploy our method on a mobile robotic system in industrial and recreational outdoor areas around the city of Berkeley. RECON can discover a new goal in a previously unexplored environment in under 10 minutes, and in the process build a “mental map” of that environment that allows it to then reach goals again in just 20 seconds. Additionally, we make this real-world offline dataset publicly available for use in future research.

Rapid Exploration Controllers for Outcome-driven Navigation

RECON, or Rapid Exploration Controllers for Outcome-driven Navigation, explores new environments by “imagining” potential goal images and attempting to reach them. This exploration allows RECON to incrementally gather information about the new environment.

Our method consists of two components that enable it to explore new environments. The first component is a learned representation of goals. This representation ignores task-irrelevant distractors, allowing the agent to quickly adapt to novel settings. The second component is a topological graph. Our method learns both components using datasets or real-world robot interactions gathered in prior work. Leveraging such large datasets allows our method to generalize to new environments and scale beyond the original dataset.

Learning to Represent Goals

A useful strategy to learn complex goal-reaching behavior in an unsupervised manner is for an agent to set its own goals, based on its capabilities, and attempt to reach them. In fact, humans are very proficient at setting abstract goals for themselves in an effort to learn diverse skills. Recent progress in reinforcement learning and robotics has also shown that teaching agents to set its own goals by “imagining” them can result in learning of impressive unsupervised goal-reaching skills. To be able to “imagine”, or sample, such goals, we need to build a prior distribution over the goals seen during training.

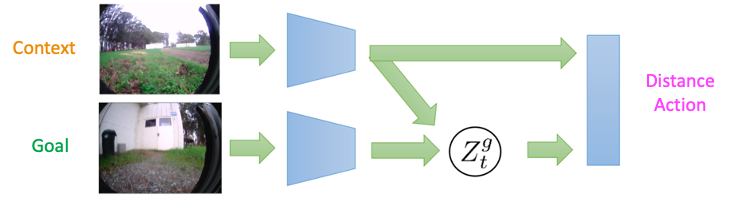

For our case, where goals are represented by high-dimensional images, how should we sample goals for exploration? Instead of explicitly sampling goal images, we instead have the agent learn a compact representation of latent goals, allowing us to perform exploration by sampling new latent goal representations, rather than by sampling images. This representation of goals is learned from context-goal pairs previously seen by the robot. We use a variational information bottleneck to learn these representations because it provides two important properties. First, it learns representations that throw away irrelevant information, such as lighting and pixel noise. Second, the variational information bottleneck packs the representations together so that they look like a chosen prior distribution. This is useful because we can then sample imaginary representations by sampling from this prior distribution.

The architecture for learning a prior distribution for these representations is shown below. As the encoder and decoder are conditioned on the context, the representation ![]() only encodes information about relative location of the goal from the context – this allows the model to represent feasible goals. If, instead, we had a typical VAE (in which the input images are autoencoded), the samples from the prior over these representations would not necessarily represent goals that are reachable from the current state. This distinction is crucial when exploring new environments, where most states from the training environments are not valid goals.

only encodes information about relative location of the goal from the context – this allows the model to represent feasible goals. If, instead, we had a typical VAE (in which the input images are autoencoded), the samples from the prior over these representations would not necessarily represent goals that are reachable from the current state. This distinction is crucial when exploring new environments, where most states from the training environments are not valid goals.

The architecture for learning a prior over goals in RECON. The context-conditioned embedding learns to represent feasible goals.

The architecture for learning a prior over goals in RECON. The context-conditioned embedding learns to represent feasible goals.

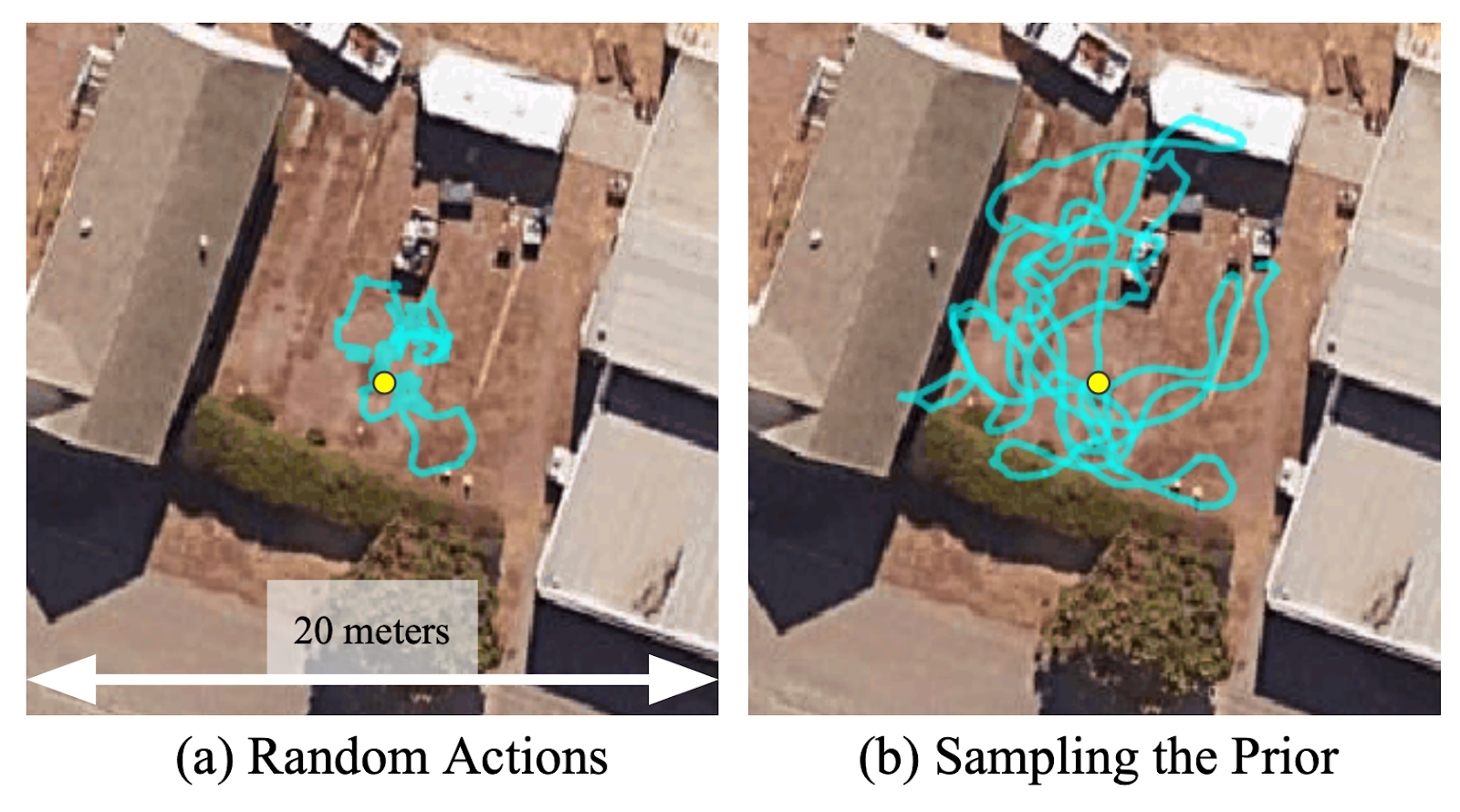

To understand the importance of learning this representation, we run a simple experiment where the robot is asked to explore in an undirected manner starting from the yellow circle in the figure below. We find that sampling representations from the learned prior greatly accelerates the diversity of exploration trajectories and allows a wider area to be explored. In the absence of a prior over previously seen goals, using random actions to explore the environment can be quite inefficient. Sampling from the prior distribution and attempting to reach these “imagined” goals allows RECON to explore the environment efficiently.

Sampling from a learned prior allows the robot to explore 5 times faster than using random actions.

Sampling from a learned prior allows the robot to explore 5 times faster than using random actions.

Goal-Directed Exploration with a Topological Memory

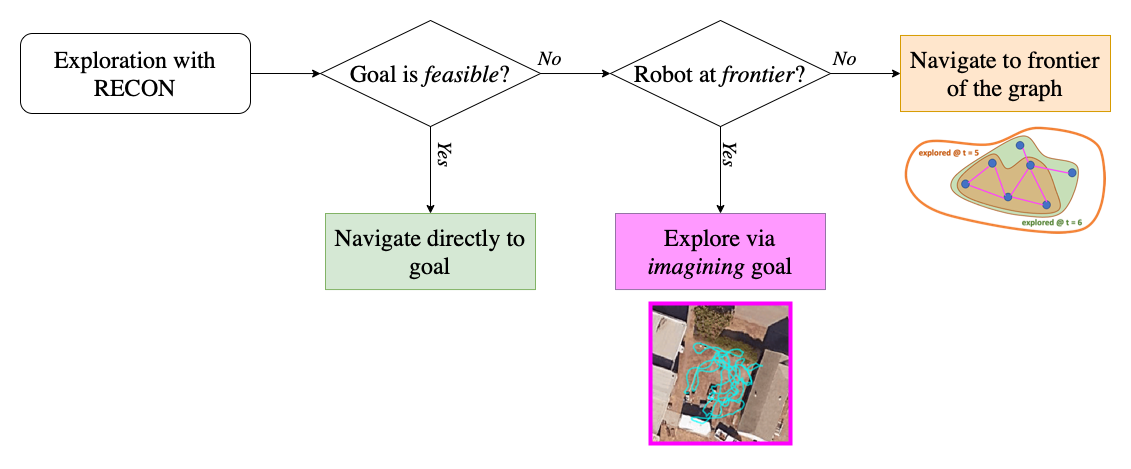

We combine this goal sampling scheme with a topological memory to incrementally build a “mental map” of the new environment. This map provides an estimate of the exploration frontier as well as guidance for subsequent exploration. In a new environment, RECON encourages the robot to explore at the frontier of the map – while the robot is not at the frontier, RECON directs it to navigate to a previously seen subgoal at the frontier of the map.

At the frontier, RECON uses the learned goal representation to learn a prior over goals it can reliably navigate to and are thus, feasible to reach. RECON uses this goal representation to sample, or “imagine”, a feasible goal that helps it explore the environment. This effectively means that, when placed in a new environment, if RECON does not know where the target is, it “imagines” a suitable subgoal that it can drive towards to explore and collects information, until it believes it can reach the target goal image. This allows RECON to “search” for the goal in an unknown environment, all the while building up its mental map. Note that the objective of the topological graph is to build a compact map of the environment and encourage the robot to reach the frontier; it does not inform goal sampling once the robot is at the frontier.

Illustration of the exploration algorithm of RECON.

Illustration of the exploration algorithm of RECON.

Learning from Diverse Real-world Data

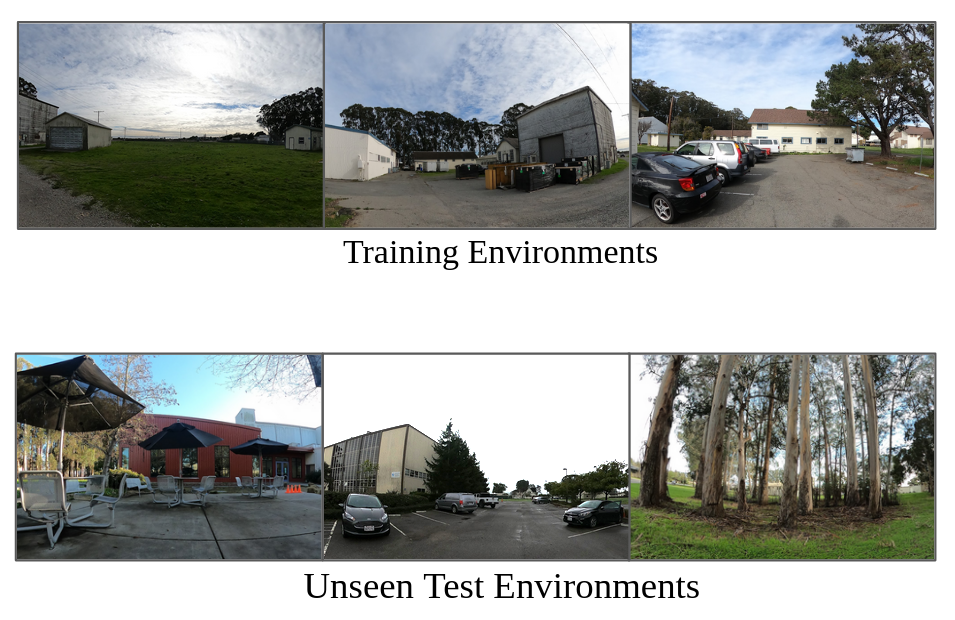

We train these models in RECON entirely using offline data collected in a diverse range of outdoor environments. Interestingly, we were able to train this model using data collected for two independent projects in the fall of 2019 and spring of 2020, and were successful in deploying the model to explore novel environments and navigate to goals during late 2020 and the spring of 2021. This offline dataset of trajectories consists of over 40 hours of data, including off-road navigation, driving through parks in Berkeley and Oakland, parking lots, sidewalks and more, and is an excellent example of noisy real-world data with visual distractors like lighting, seasons (rain, twilight etc.), dynamic obstacles etc. The dataset consists of a mixture of teleoperated trajectories (2-3 hours) and open-loop safety controllers programmed to collect random data in a self-supervised manner. This dataset presents an exciting benchmark for robotic learning in real-world environments due to the challenges posed by offline learning of control, representation learning from high-dimensional visual observations, generalization to out-of-distribution environments and test-time adaptation.

We are releasing this dataset publicly to support future research in machine learning from real-world interaction datasets, check out the dataset page for more information.

We train from diverse offline data (top) and test in new environments (bottom).

We train from diverse offline data (top) and test in new environments (bottom).

RECON in Action

Putting these components together, let’s see how RECON performs when deployed in a park near Berkeley. Note that the robot has never seen images from this park before. We placed the robot in a corner of the park and provided a target image of a white cabin door. In the animation below, we see RECON exploring and successfully finding the desired goal. “Run 1” corresponds to the exploration process in a novel environment, guided by a user-specified target image on the left. After it finds the goal, RECON uses the mental map to distill its experience in the environment to find the shortest path for subsequent traversals. In “Run 2”, RECON follows this path to navigate directly to the goal without looking around.

In “Run 1”, RECON explores a new environment and builds a topological mental map. In “Run 2”, it uses this mental map to quickly navigate to a user-specified goal in the environment.

In “Run 1”, RECON explores a new environment and builds a topological mental map. In “Run 2”, it uses this mental map to quickly navigate to a user-specified goal in the environment.

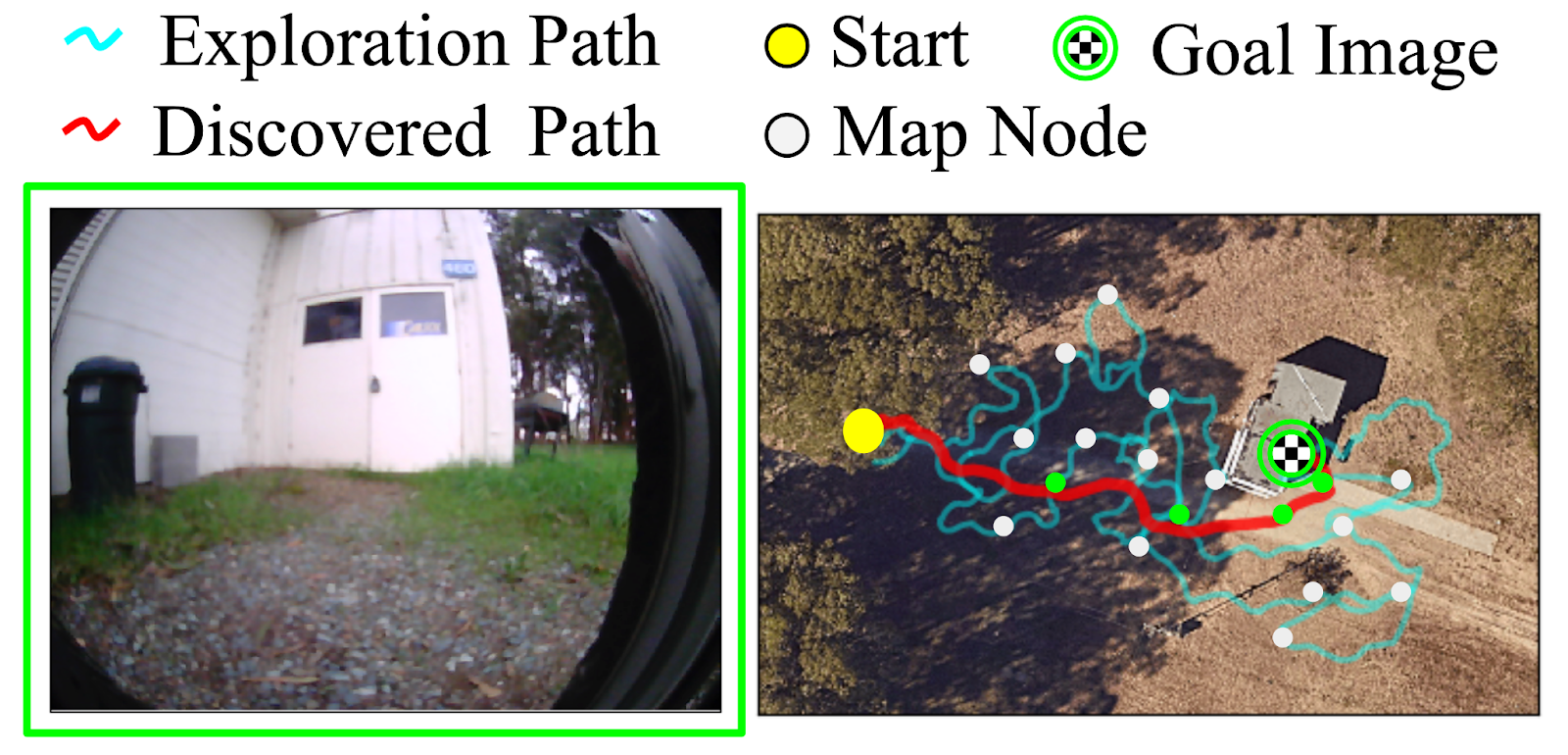

An illustration of this two-step process from an overhead view is show below, showing the paths taken by the robot in subsequent traversals of the environment:

(Left) The goal specified by the user. (Right) The path taken by the robot when exploring for the first time (shown in cyan) to build a mental map with nodes (shown in white), and the path it takes when revisiting the same goal using the mental map (shown in red).

(Left) The goal specified by the user. (Right) The path taken by the robot when exploring for the first time (shown in cyan) to build a mental map with nodes (shown in white), and the path it takes when revisiting the same goal using the mental map (shown in red).

Deploying in Novel Environments

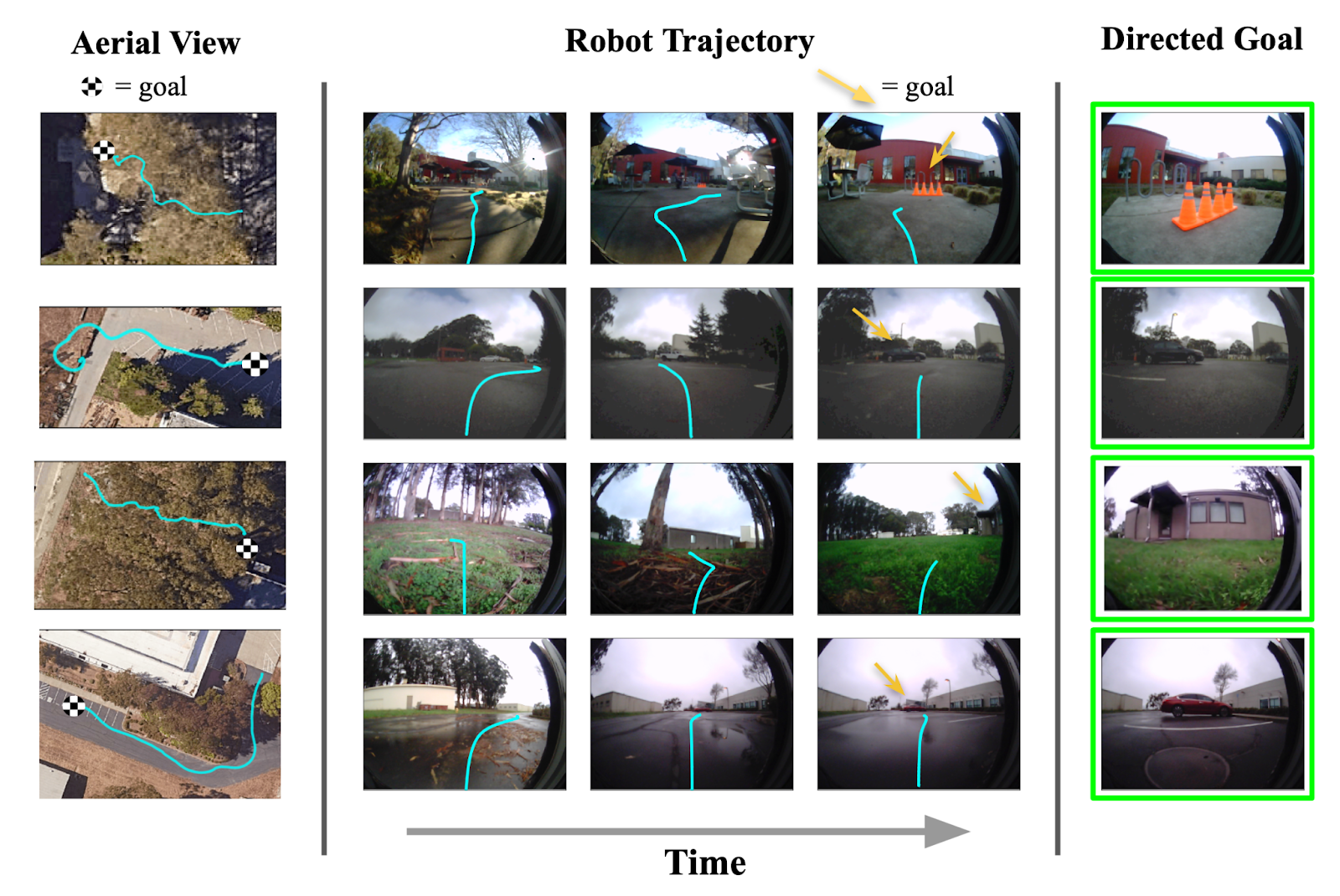

To evaluate the performance of RECON in novel environments, study its behavior under a range of perturbations and understand the contributions of its components, we run extensive real-world experiments in the hills of Berkeley and Richmond, which have a diverse terrain and a wide variety of testing environments.

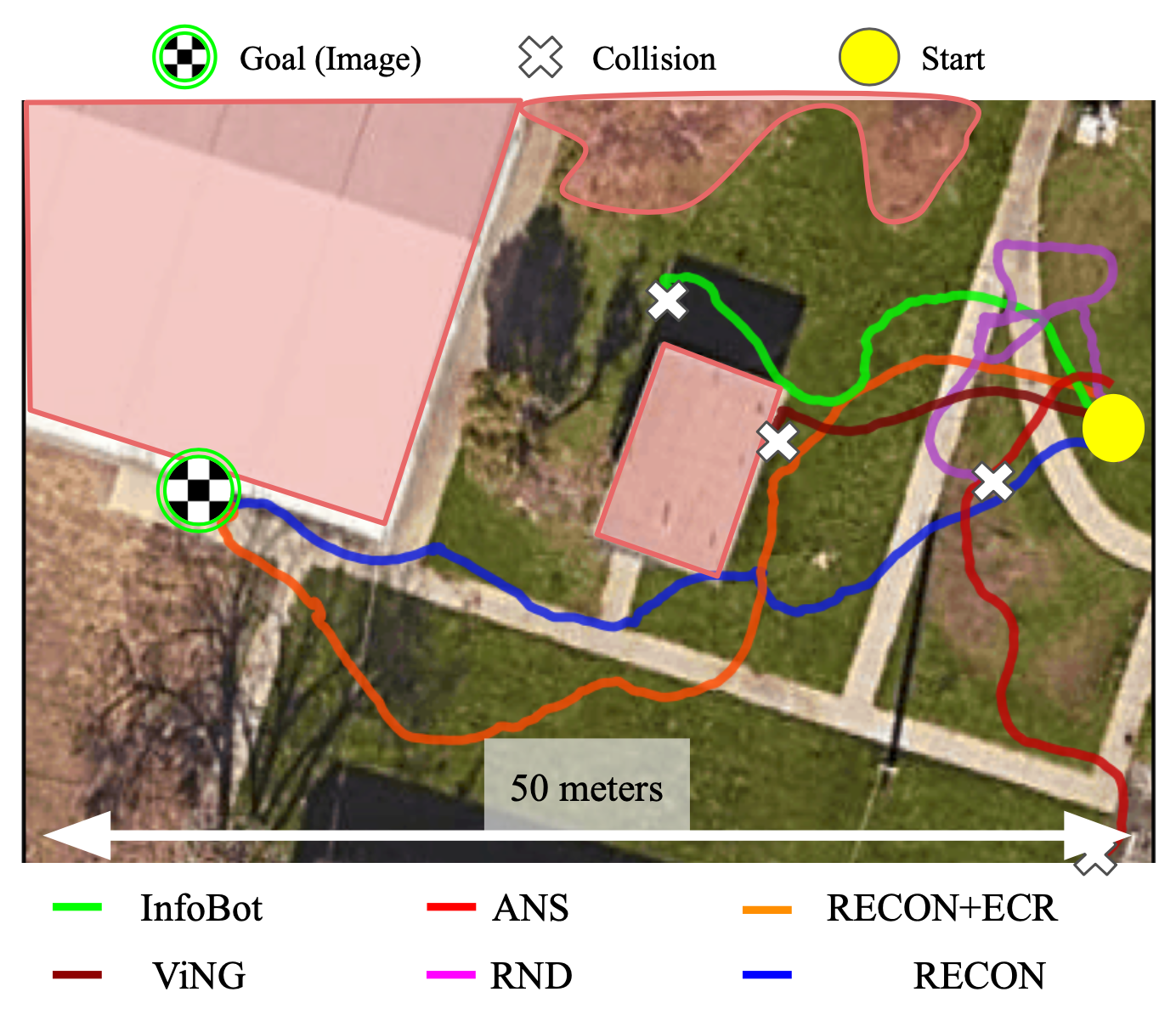

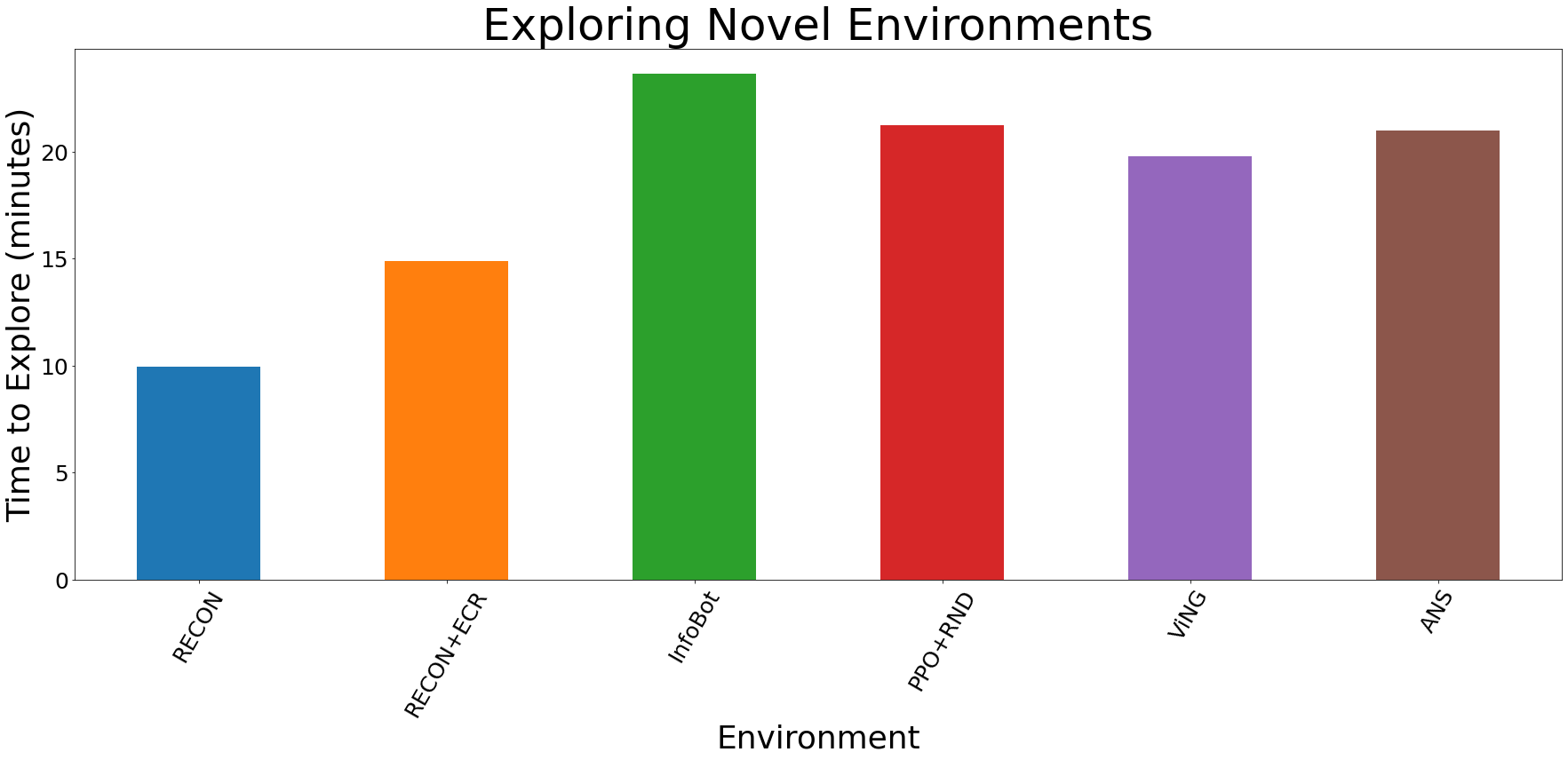

We compare RECON to five baselines – RND, InfoBot, Active Neural SLAM, ViNG and Episodic Curiosity – each trained on the same offline trajectory dataset as our method, and fine-tuned in the target environment with online interaction. Note that this data is collected from past environments and contains no data from the target environment. The figure below shows the trajectories taken by the different methods for one such environment.

We find that only RECON (and a variant) is able to successfully discover the goal in over 30 minutes of exploration, while all other baselines result in collision (see figure for an overhead visualization). We visualize successful trajectories discovered by RECON in four other environments below.

(Top) When comparing to other baselines, only RECON is able to successfully find the goal. (Bottom) Trajectories to goals in four other environments discovered by RECON.

(Top) When comparing to other baselines, only RECON is able to successfully find the goal. (Bottom) Trajectories to goals in four other environments discovered by RECON.

Quantitatively, we observe that our method finds goals over 50% faster than the best prior method; after discovering the goal and building a topological map of the environment, it can navigate to goals in that environment over 25% faster than the best alternative method.

Quantitative results in novel environments. RECON outperforms all baselines by over 50%.

Quantitative results in novel environments. RECON outperforms all baselines by over 50%.

Exploring Non-Stationary Environments

One of the important challenges in designing real-world robotic navigation systems is handling differences between training scenarios and testing scenarios. Typically, systems are developed in well-controlled environments, but are deployed in less structured environments. Further, the environments where robots are deployed often change over time, so tuning a system to perform well on a cloudy day might degrade performance on a sunny day. RECON uses explicit representation learning in attempts to handle this sort of non-stationary dynamics.

Our final experiment tested how changes in the environment affected the performance of RECON. We first had RECON explore a new “junkyard” to learn to reach a blue dumpster. Then, without any more supervision or exploration, we evaluated the learned policy when presented with previously unseen obstacles (trash cans, traffic cones, a car) and weather conditions (sunny, overcast, twilight). As shown below, RECON is able to successfully navigate to the goal in these scenarios, showing that the learned representations are invariant to visual distractors that do not affect the robot’s decisions to reach the goal.

First-person videos of RECON successfully navigating to a “blue dumpster” in the presence of novel obstacles (above) and varying weather conditions (below).

First-person videos of RECON successfully navigating to a “blue dumpster” in the presence of novel obstacles (above) and varying weather conditions (below).

What’s Next?

The problem setup studied in this paper – using past experience to accelerate learning in a new environment – is reflective of several real-world robotics scenarios. RECON provides a robust way to solve this problem by using a combination of goal sampling and topological memory.

A mobile robot capable of reliably exploring and visually observing real-world environments can be a great tool for a wide variety of useful applications such as search and rescue, inspecting large offices or warehouses, finding leaks in oil pipelines or making rounds at a hospital, delivering mail in suburban communities. We demonstrated simplified versions of such applications in an earlier project, where the robot has prior experience in the deployment environment; RECON enables these results to scale beyond the training set of environments and results in a truly open-world learning system that can adapt to novel environments on deployment.

We are also releasing the aforementioned offline trajectory dataset, with hours of real-world interaction of a mobile ground robot in a variety of outdoor environments. We hope that this dataset can support future research in machine learning using real-world data for visual navigation applications. The dataset is also a rich source of sequential data from a multitude of sensors and can be used to test sequence prediction models including, but not limited to, video prediction, LiDAR, GPS etc. More information about the dataset can be found in the full-text article.

This blog post is based on our paper Rapid Exploration for Open-World Navigation with Latent Goal Models, which will be presented as an Oral Talk at the 5th Annual Conference on Robot Learning in London, UK on November 8-11, 2021. You can find more information about our results and the dataset release on the project page.

Big thanks to Sergey Levine and Benjamin Eysenbach for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

tags: c-Research-Innovation

BAIR Blog is the official blog of the Berkeley Artificial Intelligence Research (BAIR) Lab.