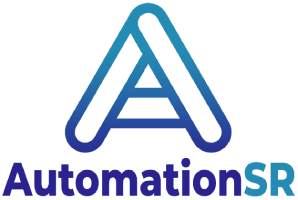

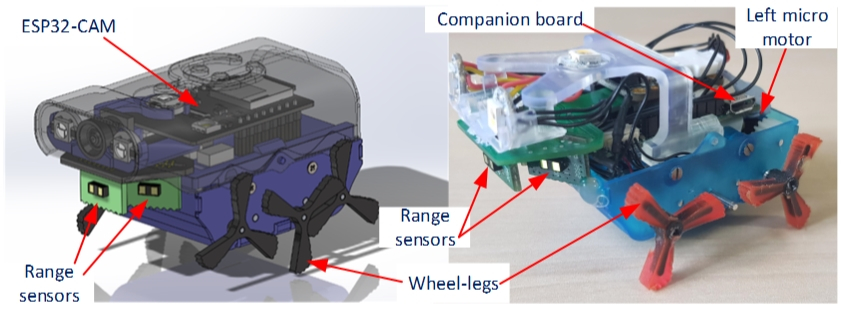

Joey’s design. Image credit: TL Nguyen, A Blight, A Pickering, A Barber, GH Jackson-Mills, JH Boyle, R Richardson, M Dogar, N Cohen

By Mischa Dijkstra, Frontiers science writer

Researchers from the University of Leeds have developed the first mini-robot, called Joey, that can find its own way independently through networks of narrow pipes underground, to inspect any damage or leaks. Joeys are cheap to produce, smart, small, and light, and can move through pipes inclined at a slope or over slippery or muddy sediment at the bottom of the pipes. Future versions of Joey will operate in swarms, with their mobile base on a larger ‘mother’ robot Kanga, which will be equipped with arms and tools for repairs to the pipes.

Beneath our streets lies a maze of pipes, conduits for water, sewage, and gas. Regular inspection of these pipes for leaks, or repair, normally requires these to be dug up. The latter is not only onerous and expensive – with an estimated annual cost of £5.5bn in the UK alone – but causes disruption to traffic as well as nuisance to people living nearby, not to mention damage to the environment.

Now imagine a robot that can find its way through the narrowest of pipe networks and relay images of damage or obstructions to human operators. This isn’t a pipedream anymore, shows a study in Frontiers in Robotics and AI by a team of researchers from the University of Leeds.

“Here we present Joey – a new miniature robot – and show that Joeys can explore real pipe networks completely on their own, without even needing a camera to navigate,” said Dr Netta Cohen, a professor at the University of Leeds and the final author on the study.

Joey is the first to be able to navigate all by itself through mazes of pipes as narrow as 7.5 cm across. Weighing just 70 g, it’s small enough to fit in the palm of your hand.

Pipebots project

The present work forms part of the ‘Pipebots’ project of the universities of Sheffield, Bristol, Birmingham, and Leeds, in collaboration with UK utility companies and other international academic and industrial partners.

First author Dr Thanh Luan Nguyen, a postdoctoral scientist at the University of Leeds who developed Joey’s control algorithms (or ‘brain’), said: “Underground water and sewer networks are some of the least hospitable environments, not only for humans, but also for robots. Sat Nav is not accessible undergound. And Joeys are tiny, so have to function with very simple motors, sensors, and computers that take little space, while the small batteries must be able to operate for long enough.”

Joey moves on 3D-printed ‘wheel-legs’ that roll through straight sections and walk over small obstacles. It is equipped with a range of energy-efficient sensors that measure its distance to walls, junctions, and corners, navigational tools, a microphone, and a camera and ‘spot lights’ to film faults in the pipe network and save the images. The prototype cost only £300 to produce.

Mud and slippery slopes

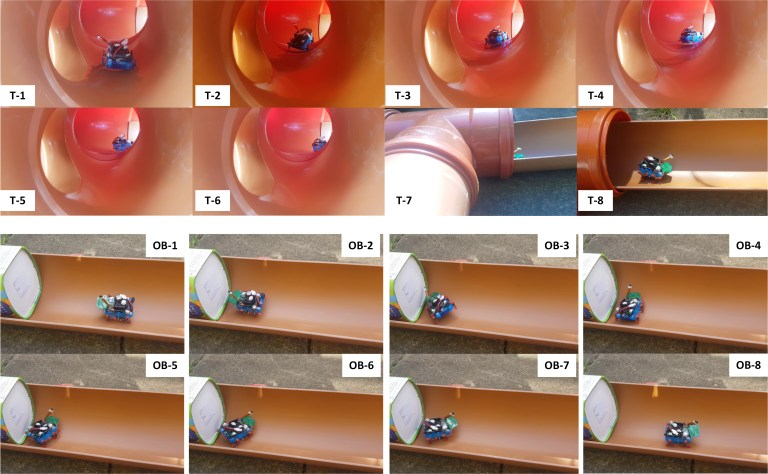

The team showed that Joey is able to find its way, without any instructions from human operators, through an experimental network of pipes including a T-junction, a left and right corner, a dead-end, an obstacle, and three straight sections. On average, Joey managed to explore about one meter of pipe network in just over 45 seconds.

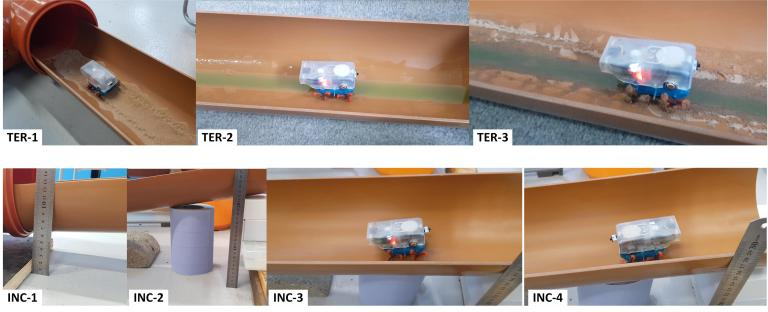

To make life more difficult for the robot, the researchers verified that the robot easily moves up and down inclined pipes with realistic slopes. And to test Joey’s ability to navigate through muddy or slippery tubes, they also added sand and gooey gel (actually dishwashing liquid) to the pipes – again with success.

Importantly, the sensors are enough to allow Joey to navigate without the need to turn on the camera or use power-hungry computer vision. This saves energy and extends Joey’s current battery life. Whenever the battery runs low, Joey will return to its point of origin, to ‘feed’ on power.

Currently, Joeys have one weakness: they can’t right themselves if they inadvertently turn on their back, like an upside-down tortoise. The authors suggest that the next prototype will be able to overcome this challenge. Future generations of Joey should also be waterproof, to operate underwater in pipes entirely filled with liquid.

Joey’s future is collaborative

The Pipebots scientists aim to develop a swarm of Joeys that communicate and work together, based off a larger ‘mother’ robot named Kanga. Kanga, currently under development and testing by some of the same authors at Leeds School of Computing, will be equipped with more sophisticated sensors and repair tools such as robot arms, and carry multiple Joeys.

“Ultimately we hope to design a system that can inspect and map the condition of extensive pipe networks, monitor the pipes over time, and even execute some maintenance and repair tasks,” said Cohen.

“We envision the technology to scale up and diversify, creating an ecology of multi-species of robots that collaborate underground. In this scenario, groups of Joeys would be deployed by larger robots that have more power and capabilities but are restricted to the larger pipes. Meeting this challenge will require more research, development, and testing over 10 to 20 years. It may start to come into play around 2040 or 2050.”

Top half: navigating through a T-junction in the pipe network. Bottom half: encountering an obstruction and turning back. Image credit: TL Nguyen, A Blight, A Pickering, A Barber, GH Jackson-Mills, JH Boyle, R Richardson, M Dogar, N Cohen

Top half: moving through sand, slippery goo, or mud. Bottom half: moving through pipe sloped at an angle. Image credit: TL Nguyen, A Blight, A Pickering, A Barber, GH Jackson-Mills, JH Boyle, R Richardson, M Dogar, N Cohen

tags: Swarming

Frontiers Journals & Blog